Introduction

The South China Sea issues continue to be the number one security and development challenge for Vietnam. In Hanoi’s view, the situation in the South China Sea relates to almost all aspects of its national security and development: protecting territorial integrity and national sovereignty, promoting maritime economic development, maintaining an external peaceful environment and particularly peaceful relationships with China and other claimants, and safeguarding regime legitimacy and internal stability. This paper examines the current situation in the South China Sea with a focus on the interactions among key players and analyzes Vietnam's responses to achieve its main objectives.

The Disputes and Challenges

There are at least four issues that Vietnam has to tackle in the South China Sea disputes: (i) sovereignty claim over “land features” in the Spratlys; (ii) sovereignty claim over “land features” in the Paracels; (iii) sovereignty rights and jurisdiction within Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, including management and utilization of hydrocarbon, mineral resources, and other living resources, especially fishing; and (iv) protecting the fishermen and their vessels operating in the overlapping areas of claims, particularly around the Paracels.1

Creeping and diversified challenges

Although Vietnam has overlapping claims in the South China Sea with five other parties (China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines), ASEAN claimants have implicitly reached a common understanding in maintaining the status quo of occupation, settling disputes by peaceful means and refraining from activities that can negatively affect interests of other members.2 Taiwan’s activities have mainly concentrated on its occupied island Itu Aba, the largest feature of the Spratlys, and therefore did not directly threaten Vietnam’s security in the South China Sea. On the contrary, China’s renewed assertiveness in the South China Sea since 2007 has been widely perceived within Vietnam as encroachment on its sovereignty and maritime interests. China’s assertiveness with its comprehensive approach, expanding not only military but also paramilitary and civilian activities, has raised the frequency of the occurrence of incidents in the overlapping area between the so-called “U-shaped line” covering about 80% of waters in the South China Sea and Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.

Resource exploitation (hydrocarbon and fish) in the South China Sea has become the most frequent source of tensions between China and Vietnam. During the period of China’s unilaterally declared fishing ban between May and August (imposed annually since 1999), Chinese maritime security forces have repeatedly detained Vietnamese fishermen, confiscated fishing boats and charged fines for their release. These kinds of incidents have become more frequent in the Paracels as Vietnamese fishermen have continued catching fish in their “traditional fishing ground.”

Besides activities at sea, a number of steps adopted by China was considered by Vietnam as being aimed at extending the legal basis for China on land features and maritime zones in the South China Sea and as encroachment on Vietnam’s sovereignty and jurisdiction, which led to a diplomatic protest by the Vietnamese side.

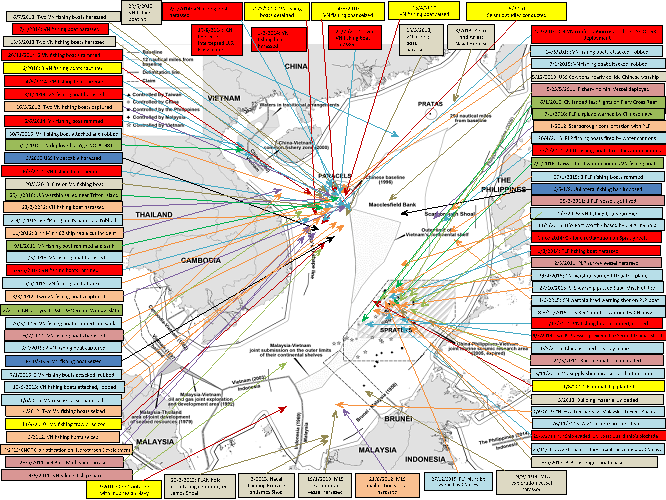

- Map: Approximate Locations of Incidents between China and other Countries in the South China Sea during 2008-2016.3

Two recent developments, specifically Chinese reclamation activities in the Spratlys and the deployment of the Chinese oil rig HYSY 981 in an area claimed by Vietnam, attracted high attention from the international community and are regarded by Vietnam as the most vivid and worrisome signs of China’s increasing assertiveness in the South China Sea.

Other developments related to the oil rig crisis have ushered in a new dimension in the Vietnamese leadership’s thinking of handling maritime issues, namely the implications of maritime disputes on economic development. For the first time, the oil rig incident not only inflamed anti-China sentiments among the Vietnamese population but also provoked large scale anti-China riots in various Vietnamese cities. The possibility of the skirmish between Chinese and Vietnamese vessels in the SCS escalating into full-scale conflict and resulting riots deteriorated the business environment in Vietnam, which until the crisis unfolded was widely considered as one of the safest and most stable in the region.

Though the incident of the deployment of the oil rig is worrisome, it was still only a short confrontation and the situation quickly renormalized. Developments in the South China Sea since 2014 involving China’s massive land reclamation and construction activities in the Spratlys have altered the status quo in the South China Sea permanently and have far-reaching strategic implications for the whole region. China’s unprecedentedly large-scale land reclamation and construction work will tremendously impact the competition among the major powers and the dynamics of the claimants’ contest in the South China Sea. China’s expanded military presence there could serve to enhance Chinese power projection capability in, if not control of, the South China Sea.

Policy of Vietnam

Since the implementation of the Doi Moi (Renovation) policy in 1986, Hanoi believed that a peaceful and favorable international environment was indispensable for economic development, and consequently, one of the main objectives of its foreign policy has been to “create a favorable international environment and conducive conditions to serve the cause of national construction and defense.”4 In dealing with the South China Sea issues, the foreign policy principle of “maintaining a peaceful environment” has been also reflected in the strategy of solving territorial and maritime disputes with other countries exclusively by peaceful means. Any confrontation with other countries relating to the disputed issues will inevitably be detrimental to the top foreign policy objective of maintaining a peaceful environment. The White Paper published in 2009 by the Ministry of Defense also reaffirms that “Vietnam’s consistent policy is to solve both historical and newly emerging disputes over territorial sovereignty on land and at sea through peaceful means on the basis of international laws.”5 At the same time, in dealing with China in the South China Sea issue, Vietnam’s objective is not allowing the struggles related to maritime issues negatively affect the cooperation aspect or overall Vietnam-China bilateral relationship.

Operationally, in response to the perception that China is increasingly encroaching on Vietnam’s maritime interests in the South China Sea, Vietnam applies the policy of a weaker party in an asymmetric relationship to defend its national interests while seeking to preserve a peaceful relationship with China. This policy is a combination of engagement and (soft and hard) balancing towards China. It is relatively comprehensive and combines several directions: (i) Direct engagement including high-level exchange, agency-to-agency interactions and direct negotiations with China on maritime issues to defuse tensions and settle remaining bilateral issues; (ii) Indirect engagement by working with other members of ASEAN to engage China in DOC implementation and head towards a new code of conduct (COC); Soft balancing consisting of (iv) bringing up the South China Sea issues in regional forums (particularly ASEAN-related forums), (v) engaging the participation of other external powers in the South China Sea issues, and (vi) using international law, especially UNCLOS 1982, to defend its maritime claims. Hard balancing is for deterrent purposes, namely (vii) improving military capacity, especially modernizing the navy, and strengthening law enforcement capability (the Coast Guard and Fishing Patrol Agency).

Direct engagement

Regarding the direct engagement component of its policy, Vietnam emphasizes the exchange of high-level visits with China and the South China Sea issues have become one of the main topics of discussion among the two countries’ leaders. In addition to high-level exchanges, Vietnam and China also established the Steering Committee on Vietnam-China Bilateral Cooperation (since 2006), and a network of engagement with China through party-to-party and agency-to-agency cooperation channels. These include cooperative measures between agencies directly and indirectly relating to the handling of maritime issues, such as militaries (exchanged visits, hot line, strategic dialogue, port call, joint naval patrol, etc.), agencies responsible for fishery cooperation, combat of transnational crimes, and border provinces. Vietnam and China have also conducted direct negotiations on unresolved maritime issues. In October 2011, during the visit of Vietnam Communist Party’s Secretary General Nguyen Phu Trong to Beijing, Vietnam and China signed the Agreement on the Basic Principles Guiding the Resolution of Maritime Issues, in which the two sides pledged to address maritime issues incrementally and speed up the demarcation and cooperation in waters off the Tonkin Gulf and foster cooperation in less sensitive fields including marine environmental protection, marine science research, search and rescue operations, and natural disaster mitigation and prevention.6 Most recently, during the first official visit by Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc to China at the invitation of Chinese Premier Li Keqiang from September 10 to 15, 2016, Phuc met with Chinese President Xi Jinping, had talks with Li and held a number of meetings with other high-ranking leaders. During the talks and meetings, Vietnam News Agency reported that the Vietnamese and Chinese leaders agreed on the following:

They will control and satisfactorily handle existing disagreements and arising problems, while fostering the healthy and stable development of the comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership, thereby practically benefiting the two peoples and contributing to peace, stability and prosperity in the region.

The two sides agreed to seriously implement the bilateral agreement on basic principles guiding the settlement of sea-related issues, and, together with ASEAN countries, comprehensively and effectively carry out the DOC, and resolve disputes by peaceful measures on the basis of international law, including UNCLOS 1982.7

Some Vietnamese analysts believe that by bringing up the South China Sea issues into high-level discussions, these issues can be elevated to a higher level of priority in China’s foreign policy, encouraging Chinese leaders to put the issues in a broader picture of bilateral and regional relations and better manage the competition among various interest groups within China – one of the main sources of tensions in recent years. These engagements are also expected to promote mutual trust, cooperation and minimize misunderstanding among interest groups of both sides. On the other hand, cooperative mechanisms among agencies directly dealing with maritime issues can arguably help both sides prevent incidents from happening and/or to deescalate tensions. However, it should be noted that the main competition between Vietnam and China in the South China Sea in recent years is between law enforcements agencies for protecting (and preventing development) of resources (hydrocarbon and fish), but both sides have not yet established any cooperative and dialogue mechanisms between their Coast Guards. From May to July 2014, despite Vietnam’s continuous efforts to use high-level meetings, the hot-line and “more than fifty” diplomatic communications with China to resolve the crisis relating to the placement of China’s HYSY 981 oil rig, the relatively long duration of the crisis indicated the limit of bilateral direct engagement in deescalating tensions. China withdrew the oil rig one month before the originally-planned time but it was arguably not as a result of bilateral Vietnam-China direct engagement.

Instead, bilateral Vietnam-China direct engagement has proven to be more helpful in restoring the damaged relationship once the crisis was over. After China withdrew the oil-rig, both sides exchanged a number of significant visits and meetings by leaders and high-ranking officials to renormalize the relationships and promote practical cooperation. As a result, by the end of 2014, the bilateral relationship had returned to a new normal.

On the bilateral relationship with China, as mentioned above, Vietnam’s policy is to separate two aspects of the relationship so that the struggling maritime issues will not negatively affect the cooperation aspect or overall bilateral relationship. For example, while demonstrating its determination in confronting China over deployment of oil rig HYSY 981 in its exclusive economic zone during May to July 2014, Hanoi still maintained communication linkage on a different level with Chinese counterparts and successfully managed to keep commercial and investment cooperation (except tourism) unaffected. In addition, soon after the oil rig crisis was over, Vietnam took the decision to join and become one of the founding members of the Chinese-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).8

At the same time, isolating the issues of conflicting interests from negatively affecting cooperation and the overall bilateral relationship has become a challenging task. In particular, the issue of the South China Sea dispute is similar to a cancer that cannot be isolated and, therefore, affects all activities of the body. The more China becomes assertive in the South China Sea (or regarded as assertive in Vietnam’s perspective), the more anti-Chinese sentiment there is among the Vietnamese people within and without the country. According to Pew Research surveys, 78 percent in 2014 and 74 percent in 2015 of Vietnamese people hold an unfavorable view for China.9 As Vietnam incrementally and increasingly becomes more democratic, its government has to take into account public opinion and no one wants to appear soft in protecting national sovereignty or appear to be overly accommodating toward China. During the oil rig crisis in 2014, then Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung received nationwide endorsement when he declared that “we cannot trade our sacred independence and sovereignty for some elusive peace or any type of dependence.”10 Due to the maritime territorial dispute, the idea of sharing ideologies between Vietnam and China has also become irrelevant in today’s context.

Due to the negative spill-over effects of maritime disputes, a number of Vietnam experts also perceive economic proposals from China with suspicion and see strategic intentions behind them. Looking at China’s grand initiative of “One Belt One Road” (OBOR), for example, they see that behind this initiative China can advance its sovereignty propaganda with its creation of a maritime Silk Road. Realizing OBOR could deepen the economic dependence of Vietnam and other ASEAN members on China, and, therefore, lower these countries’ positions and standing in forming consensus among ASEAN on South China Sea issues.

Indirect engagement

Regarding indirect engagement, Vietnam tried to work with other ASEAN members to collectively engage China in multilateral discussion of the South China Sea within the framework of ASEAN-China dialogue and in Declaration of Conduct (DOC) implementation, and head towards a new Code of Conduct (COC). This indirect engagement is widely considered as one of the most important components of Vietnam’s overall strategy toward the South China Sea issues.

Hanoi understands the internal and external dynamics of ASEAN. Due to divergent interests and external pressures, ASEAN countries have different viewpoints regarding the South China Sea issues. While acknowledging that ASEAN countries have divergent interests on the South China Sea, Vietnam has made continuous efforts to work with member states to maintain at least minimum denominators on this issue. In fact, all ten ASEAN member states participated in negotiation and signed the DOC in 2002 and they all also reached consensus to promote the negotiation of the COC with China in order to effectively manage the disputes and enhance peace and cooperation in the region.11 While working toward the COC, Vietnam sees the DOC 2002 as still being one of the most important documents (in addition to UNCLOS 1982) to regulate behaviors of parties in the South China Sea, despite the fact that it is a political document and not legally binding. Though some of the DOC’s provisions are ambiguous and open for parties to criticize each other for its violations, the more clearly stated provisions, such as no use of force or no new inhabitation on unoccupied islands/rocks in the South China Sea, to a certain extent, have helped prevent China from conducting adventurist activities. The process of DOC implementation and negotiation on COC arguably has facilitated China’s engagement with discussing the South China Sea issue within the ASEAN-China framework.

At the same time, Vietnam understands the limits of indirect engagement with China through the ASEAN framework as it requires not only consensus within ASEAN but also, more importantly, the political will from Beijing to accept some common understanding on the issue of the South China Sea. The three-level game of negotiation (internally within one country, within ASEAN, and between ASEAN and China) explains why the process of concluding any document is so protracted. For example, ASEAN took more than seven years to engage China in negotiating the DOC, which was signed in 2002,12 and almost nine years to complete the symbolic Guidelines for the implementation of the DOC, which was agreed in July 2011.13 Moreover, despite the original purpose of avoiding incidents at sea among law enforcement forces by application of the Code of Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) for Coast Guards in the South China Sea, due to objection from China, ASEAN was only able to get the former’s signature on the joint statement for application of CUES only for naval ships and naval aircrafts.14 This joint statement, therefore, has only symbolic meaning given that all claimant states had already adopted CUES within the framework of the Western Pacific Naval Symposium (WPNS). Similarly, the future of ongoing negotiations/consultation on the COC remains uncertain and possibly protracted as ASEAN hopes to engage China in accepting a binding agreement that will, among others, regulate China’s behaviors in the South China Sea. Nevertheless, for ASEAN, the process of engagement with China is equally as important as the results.

Soft and hard balancing

As discussed above, although direct engagement and indirect engagement through ASEAN provides useful channels for Vietnam in dealing with China on the South China Sea issues, it is not sufficient to prevent China from advancing its claims there. Therefore, Vietnam has to rely also on soft and hard balancing elements of its strategy. Its soft balancing consisted of bringing up the South China Sea issues in regional forums, particularly in ASEAN-related forums; engaging the participation of other major powers in the South China Sea; and using international law, especially UNCLOS 1982, to defend its maritime claims and settle the disputes by peaceful means.

Major power engagement

Since the 1990s, Vietnam has adopted a foreign policy of diversification and multilateralization of external relations, in which major powers play very important roles in strengthening its autonomy, security and development. Some Vietnamese analysts see one of the positive implications of that process in the intertwining of the interests of major powers in the country, and consequently, Vietnam’s possible competitors have to take into account the interests of these major powers as well. In these circumstances, the possibility of using military actions to solve the territorial disputes can be narrowed.15

Specifically, highlighting the South China Sea issues in regional forums with the participation of other countries who also share converged concerns and interests could become a feasible approach to influence China’s calculations. If the issues were to become one of the main concerns in China’s external relations, it would force China to contemplate its other interests in relations with major powers and, thus, adjust its approach in the South China Sea. As a result, the South China Sea issue would be given elevated priority in China’s foreign policy decision-making process, and, consequently, competition between and independent activities of China’s interest groups, which is one of the main reasons behind the renewed tensions since 2007, would become manageable.16

Among major powers, the United States is considered as one of the most important partners to Vietnam. Some Vietnam analysts believed that although the United States conducts its activities in the South China Sea according to its own interests, U.S. involvement has increased Vietnam’s leverage in relation to China, making China soften its assertive approach and less willing to use force to solve the territorial disputes. In addition, U.S. policy has spill-over effects on the positions of other countries, especially countries that have close relationships with Washington, encouraging these stakeholders (such as Japan, Australia, India, and some European countries) to express concerns about developments in the South China Sea at many multilateral mechanisms (ARF, EAS, ADMM+, ASEM, G7, etc.).

Under the Obama administration, the United States, after a long engagement in the Middle East and Afghanistan in the war against terrorism, has “pivoted to Asia” to cope with a rising China.17 The South China Sea has become one of the main focal points of the “Asian rebalancing” strategy adopted by the Obama administration. In recent years, the United States has enhanced military and maritime cooperation with China’s competitors in maritime domains, such as Japan and the Philippines. The United States strengthened its access and readiness level in the South China Sea by signing with the Philippines the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement in April, 2014, which covers the full range of defense cooperation, including deployment of U.S. “rotational troops” on Philippine territory, developing maritime security and maritime domain awareness.18 U.S. high-ranking officials also referred to the South China Sea issues more often and with stronger substance over time in their official speeches, especially within multilateral diplomatic meetings. From 2015 to 2016, in a move to signal more direct engagement on the ground (i.e. at sea), the United States conducted three freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea to challenge the “excessive maritime claims” of parties by sending navy destroyers within 12 nautical miles of Subi Reef and Fiery Cross in the Spratly Islands and in the vicinity of Triton Island in the Paracel Islands.19

However, some Vietnam analysts see the limits of the U.S.-Vietnam relationship in the U.S.-Vietnam-China triangle. Hanoi views the relationships between the United States and China as containing both elements of “cooperation and competition.” While both are strategic competitors, Washington still needs to work with Beijing on issues of convergent interests: from the conflicts on the Korean Peninsula and in the Middle East, to economic cooperation and climate change. Therefore, some fear that in certain circumstances, Washington may trade Beijing’s cooperation on issues of convergent interests in exchange for a softening of the U.S. position toward issues critical for China such as the South China Sea issues. Therefore, Vietnam strategists are watching closely the U.S.-China interactions under new president Donald Trump, particularly in relation to concerns attributed to Trump’s gamble in softening the U.S. approach toward China across the board in exchange for China’s cooperation on North Korea’s nuclear and missile issues.

In an opposite scenario, Vietnam does not want to be forced to “take sides” and tries to avoid the possibility of being dragged into the U.S.-China strategic competition, and thus jeopardizing its independence and narrowing the room for strategic maneuver. Within the limits of the “three nos” policy of no military alliances, no alignment with one country against third parties, and no foreign military bases in its territory, Vietnam is also careful not to allow the developments in its relations with the United States to provoke China and inadvertently deteriorate bilateral relations with its biggest neighbor.20

In addition to the concerns about U.S. commitment and durability in the region due to global overreach, perceived power decline and real military budget cuts, there are also other aspects in which the U.S. involvement in the South China Sea is limited. That the United States has not yet joined UNCLOS 1982 is reducing its legitimacy to criticize other countries, particularly China, for not respecting maritime law. The increasing presence and activities of U.S. naval forces in the South China Sea, for now, could not prevent China from (but may trigger) further expansion and militarization of its occupied islands. In response to U.S. freedom of navigation operations around the Paracels, for example, China decided to deploy HQ-09 surface-to-air missiles having a range of 200 km, signaling its long-term plans to strengthen its military reach across the South China Sea.21

On other hand, the increasing presence of U.S. naval forces does not have significant impact on the contest for the control of resources in the South China Sea, which is mainly among law enforcement vessels from claimant countries. If China continues to use nonmilitary measures on the sea, and apply economic and diplomatic measures to influence ASEAN countries’ policies, the United States cannot interfere with and influence the settlement of South China Sea issues.

However, while continuing to show its various commitments, the United States could possibly respond to China’s strategy by adding other elements to its strategy such as paramilitary and economic elements, which it has relatively neglected over the years.22 Specifically, in addition to helping other countries improve their maritime surveillance and law enforcement capability, the United States may consider deploying its Coast Guard directly in the South China Sea, possibly in the name of cooperation for combatting non-traditional security threats to avoid provoking negative reactions from Beijing. The United States can help littoral states in improving their maritime domain awareness, individually or collectively, and sharing the intelligence information regarding the real picture on the ground (i.e. at sea). Regarding economic involvement, Washington should put more emphasis on the strategic aspect of economic engagement. President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Tran-Pacific Partnership (TPP) has already harmed U.S. credibility and strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific, and been even more damaging than its failure to ratify UNCLOS. The United States should work out alternatives to TPP so as to strengthen U.S. economic engagement with the region, which is the permanent base for its rebalancing strategy.

Other major powers

Among other major powers, Japan is emerging as one of the most important partners to Vietnam not just in terms of economic cooperation but also in the field of maritime cooperation and strategic concerns over China’s long-term intention. Russia is the main arms provider for Vietnam and invests heavily in oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea. Both sides upgraded relations to the comprehensive strategic partnership level in 2013. However, Russia’s main focus is on its immediate neighbors of former republics, particularly due to worsening relations with Ukraine. Southeast Asia is secondary in the list of priorities of Moscow’s foreign policy in comparison with Europe, the Middle East and Northeast Asia. Russia is also a “comprehensive strategic partner” and currently enjoys “the best relationship ever” with China,23 and strongly needs Beijing’s cooperation after suffering from Western sanctions due to its annexation of Crimea. In addition, Russia’s position that the South China Sea disputes should be resolved through bilateral negotiations, opposition third party involvement, support for China’s position on the South China Sea arbitration, conducting of bilateral military exercises with China in the South China Sea and mounting reactions to some serious incidents, particularly relating to China’s deployment of oil drilling rig HYSY 981 within Vietnam’s EEZ in 2014, all did not meet the expectations of Vietnamese counterparts. India is also involved in oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea, is improving military cooperation with Vietnam and also has territorial disputes with China, but it seems that India’s “Act East” capacity has not yet met its “Look East” aspiration.

International law

As another aspect of soft balancing, Vietnam has increasingly relied on international law, particularly UNCLOS 1982, to defend its maritime claims and settle the disputes by peaceful means. By compliance by and reliance on international law, Vietnam expects to deal with China on a more equal and less asymmetric basic. Vietnam has criticized the legal basis, if any, of China’s territorial and maritime claims and its assertive moves in the South China Sea and gained moral support from the international community. So far, Vietnam has not resorted to third-party arbitration for the settlement of maritime territorial disputes in relation with China. The possibilities of economic retaliation from China and deterioration of bilateral relations, the difficulties in getting China seriously involved in UNCLOS’s dispute settlement mechanism, the uncertainty of possible decisions by the arbitrators, and the lack of an enforcement mechanism for international arbitration all explain Vietnam’s reluctance to date in choosing this path. However, as discussed above about the limitations of direct engagement, if other soft balancing acts and also hard balancing components cannot help Vietnam in deterring China from encroachment on its maritime interests, Hanoi might seriously consider using legal means as the last peaceful resort. In fact, Vietnam supports the Philippines’ move of bringing its dispute with China to arbitration under Annex VII of UNCLOS 1982. On December 5, 2014, Vietnam submitted a statement to the arbitration panel recognizing the court's jurisdiction over the case and rejecting the nine-dotted line.24 Responding to the arbitration award on July 7, 2016, the spokesperson for the Foreign Ministry stated: “Viet Nam welcomes the fact that, on 12 July 2016, the Tribunal issued its Award in the arbitration between the Philippines and China… Viet Nam strongly supports the settlement of disputes in the East Sea by peaceful means, including legal and diplomatic processes… and respect for the rule of law in the oceans and seas.”25

During the crisis ignited by the deployment of the Chinese mega oil rig in Vietnam’s EEZ in May-July 2014, the Vietnamese government did consider various "defense options" against China, including legal actions.26 Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung ordered relevant agencies to prepare documents for legal proceedings against China for “illegally placing a drilling rig in Vietnam’s waters.”27 The sweeping victory of the Philippines in the arbitration case with the Tribunal may add more convincing arguments for those who are advocating for a legal approach in the internal debate among decision makers. Whether or not to undertake this strategic move, of course, would be the subject of careful consideration by the Vietnamese Communist Party’s Politburo.

Hard balancing

Regarding hard balancing, although Vietnam considers diplomacy as “the first line of defense” and believes in using peaceful means to resolve the disputes, rising competition in the South China Sea has induced Hanoi to invest in improving its “deterrent” capacity, with more attention given to naval and air forces.

After about a decade of inadequate investment, Vietnam is modernizing its deterrent capability through upgrading naval, air and electronic-warfare capabilities. For instance, it was widely reported that Vietnam signed contracts with Russia to buy six Project 636 Kilo-Class submarines with a value of up to U.S.$ 1.8 billion. The first and second Kilo-Class submarines were transferred to Vietnam by Russia in December 2013 and in March 2014 respectively, and the sixth is scheduled to be delivered in 2016.28 The amount of submarines and the budget expended for this procurement – almost equal to one year’s defense budget – demonstrate the seriousness with which Vietnamese leaders consider its security and sovereignty in maritime areas. Vietnam also ordered four Russian Gepard-class light frigates, specially equipped for anti-submarine warfare, and in 2011 deployed its first two. In 2012 Vietnam also finalized a contract to purchase four Sigma-class corvettes from the Netherlands. To provide air cover to its naval fleet, Vietnam is acquiring at least 20 Russian-made Su-30MK2 multi-role fighter aircrafts in addition to about a dozen relatively modern SU-27s and MiG aircrafts.29 In August, 2013, Vietnam signed a contract with Russia for the purchase of an additional twelve Sukhoi Su-30MK2 multirole jet aircraft armed with anti-ship missiles in a deal valued at U.S.$450 million.30 To improve naval surveillance and patrol, Vietnam has procured six DHC-6 Twin Otter amphibious aircraft from Canada.31 Vietnam’s new submarine force, combined with anti-submarine warfare capability, naval surveillance and patrol, and additional Su-30s is believed to enhance its anti-access/area-denial capability for protecting the country’s sovereignty and interests in the South China Sea.

At the same time, Vietnam has also strengthened bilateral and multilateral defense cooperation with other powers to deal with national security challenges. The complex nature of security threats, not just in the South China Sea, has demanded Vietnam to “expand defense diplomacy and actively participate in defense and security cooperation in the regional and international community.”32 Vietnam’s defense diplomacy actively contributes to “maintaining a peaceful and stable environment” and promoting regional cooperation. Alongside Vietnam’s policy to tackling the challenges in the South China Sea by bringing up issues of common concern in international and regional forums to engage China and other countries to collectively find solutions, Vietnam’s defense sector is also raising these issues in defense-related forums and participating in confidence-building processes, such as ADMM and ADMM+.

Improvement of law enforcement capability

The other aspect of hard balancing is improvement of law enforcement capability. Vietnam considers military confrontation to be unlikely in the near future and the main competition in the South China Sea to be between law enforcement forces. In 2013, the Marine Police, which was established in 1998, was restructured, renamed as the “Coast Guard” and placed under the direct command of a Member of Cabinet, specifically the Minister of Defense, instead of being an agency under the Ministry of Defense. This restructuring was aimed at avoiding any blame for using military vessels for law enforcement purposes and for expanding international cooperation with the Coast Guards of other countries. In 2013 Vietnam also established the Vietnam Fisheries Resources Surveillance (under the Vietnam Directorate of Fisheries) with a view to better protecting the country’s sovereign rights relating to fisheries within its exclusive economic zones.33 The deployment of law enforcement vessels is prioritized in contested areas during confrontations to serve two purposes: demonstrating the country’s sovereignty right and jurisdiction and avoiding possible escalation or even military clash if using naval vessels. For example, from May to August 2014, during the skirmish around the placement of mega oil rig HYSY 981 within its exclusive economic zone, Vietnam deployed more than thirty government ships from the Coast Guard and Fisheries Resources Surveillance to confront Chinese vessels (while naval assets were kept far in the distance).34

Vietnam is also expanding international cooperation to improve its law enforcement capability with major countries that share Vietnam’s concerns about China’s maritime expansion. For example, in 2013, Vietnam and Japan reached an agreement in which Tokyo would transfer patrol vessels to Vietnam to help strengthen maritime security capability.35 On August 1, 2014, Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida announced during his visit to Hanoi that Japan would provide Vietnam with six used vessels to boost the maritime patrolling capability of the Vietnam Coast Guard and Fishery Surveillance Force.36 During his visit to Vietnam in December 2013, then U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry also announced the U.S. decision to provide assistance for maritime security capability to Vietnam amounting to U.S.$18 million (within an additional U.S.$32.5 million to help Southeast Asian nations), including fast patrol boats to the Vietnam Coast Guard.37 On May 22, 2017, U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Ted Osius officially handed over six of the 45-foot Metal Shark patrol boats to the Vietnam Coast Guard (VCG) in Quang Nam, Region II.38 In April 2014, amid China’s rising assertiveness in the South China Sea, the United States and Japan jointly declared their intention to collaboratively assist ASEAN’s littoral states “in building maritime domain awareness and other capacities for maritime safety and security so that they can better enforce law, combat illicit trafficking and weapons proliferation, and protect marine resources.”39

Conclusion

Vietnam’s policy of combining engagement and (soft and hard) balancing in dealing with China’s assertive strategy in the South China Sea is still widely considered as the most effective strategy to defend Vietnam’s national interests while simultaneously preserving a non-confrontational and peaceful relationship with China, enhancing Vietnam’s role within ASEAN, and promoting cooperation with other major powers including the United States, Japan and other South China Sea stakeholders. Vietnam’s strategic room for maneuver has not yet reached its limits, particularly with regard to two specific directions: using the international law channel and promoting cooperation with other stakeholders. If other soft balancing acts and also hard balancing measures cannot help Vietnam deter Chinese encroachment on its national interests, Hanoi might seriously consider using legal means as the last peaceful resort. Additionally, while walking a delicate balance between China and the United States, Vietnam will develop its relationship with the United States to the extent that such development does not court confrontation with China. China’s policy towards Vietnam in the South China Sea will be a determining factor for Vietnam’s policy of maintaining an appropriate balance between nurturing bonds with the United States and keeping ties with China.

1 Tran Truong Thuy & Nguyen Minh Ngoc, “Vietnam's Security Challenges: Priorities, Policy Implications and Prospects for Regional Cooperation,” in Security Outlook of the Asia Pacific Countries and Its Implications for the Defense Sector, edited by National Institute for Defense Studies (Tokyo: National Institute for Defense Studies, 2013), p.96, at http://www.nids.go.jp/english/publication/joint_research/series9/pdf/08.pdf.

2 In addition to the Agreement with China on the Delimitation of the Tonkin Gulf and on Fishery Cooperation on December 25, 2000, Vietnam has signed the Agreement with Thailand on Maritime Delimitation on August 9, 1997 and the Agreement with Indonesia on the Delimitation of Continental Shelf on June 26, 2003. Vietnam is currently involved in negotiations with Indonesia on the delimitation of their exclusive economic zones. As for cooperation with neighboring countries, in 1992, Vietnam signed with Malaysia an MOU for cooperation in exploration and exploitation of petroleum in a defined area of the continental shelf involving the two countries in the Gulf of Thailand, which has been effectively implemented, and is currently engaged in negotiations with Thailand and Malaysia on cooperation in the Tripartite Overlapping Continental Shelf Claim Area. In early May 2009, Vietnam, in cooperation with Malaysia, submitted to the United Nations the Submission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf beyond 200 nm in the Southern part of the South China Sea. See, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Vietnam – a responsible party of UNCLOS Convention,” at http://english.vov.vn/Politics/East-Sea/Vietnam-a-responsible-party-of-UNCLOS-Convention/251426.vov.

3 Compiled by the author based on press reports (VN: Vietnam; PLP: Philippines; MLS: Malaysia)

4 See the text of the 13th Politburo Resolution, May 1988; Nguyen Co Thach’s Interview with Journal of International Relations Studies, January 1990, Movements in the World and Our New Perspective; reprinted in Nguyen Vu Tung, Vietnam’ s Foreign Policy 1975-2006, Institute of International Relations, Hanoi, 2007, p. 42.

5 Ministry of Defence, Defence White Paper 2009, p19, at http://admm.org.vn/sites/eng/Pages/vietnamnationaldefence%28vietnamwhitepapers-nd-14440.html?cid=236.

6 “Vietnam-China agree on basic principles to resolve maritime issues,” at http://en.nhandan.org.vn/en/politics/external-relations/item/1808602-vietnam-china-agree-on-basic-principles-to-resolve-maritime-issues.html.

7 PM Nguyen Xuan Phuc finishes tour of China, at http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/government/163782/pm-nguyen-xuan-phuc-finishes-tour-of-china.html.

8 Vietnam joins AIIB to seek new funding source, http://english.thesaigontimes.vn/41699/Vietnam-joins-AIIB-to-seek-new-funding-source.html.

9 http://www.pewglobal.org/database/indicator/24/country/239/response/Unfavorable/.

10 http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/13/opinion/sunday/vietnams-overdue-alliance-with-america.html?_r=0.

11 In July 2012, ASEAN foreign ministers reached a consensus and adopted the “proposed elements” of the COC and tasked the ASEAN senior officials to meet with the senior official from China to negotiate on the code. Michael Lipin, “Cambodia Says ASEAN Ministers Agree to ‘Key Elements’ of Sea Code,” Voice of America, July 9, 2012, at http://www.voanews.com/content/cambodia_asean_ministers_agree_to_key_elements_of_sea_code/1381574.html.

12 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, ASEAN website, at http://www.asean.org/asean/external-relations/china/item/declaration-on-the-conduct-of-parties-in-the-south-china-sea.

13 “Guidelines for the Implementation of the DOC,” ASEAN website, http://www.asean.org/documents/20185-DOC.pdf.

14 Joint Statement on the Application of the Code of Unplanned Encounters at Sea in the South China Sea, September, 7, 2016; see full text at http://asean.org/storage/2016/09/Joint-Statement-on-the-Application-of-CUES-in-the-SCS-Final.pdf.

15 Interview with the author

16 In March 2013, China announced plans to restructure the country's top oceanic administration by bringing China's maritime law enforcement forces, currently scattered in different ministries, under the unified management of one single administration, to “enhance maritime law enforcement and better protect and use its oceanic resources.” See “China to restructure oceanic administration, enhance maritime law enforcement,” Xinhuanet, October 10, 2013, at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-03/10/c_132221768.htm.

17 Hillary Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy, October 11, 2011, at http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/10/11/americas_pacific_century.

18 “Q&A on the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement,” at http://www.gov.ph/2014/04/28/qna-on-the-enhanced-defense-cooperation-agreement/.

19 “Return of the FONOP: U.S. Navy Destroyer Asserts Freedom of Navigation in Paracel Islands,” at http://thediplomat.com/2016/01/return-of-the-fonop-us-navy-destroyer-asserts-freedom-of-navigation-in-paracel-islands/.

20 Nguyen Tan Dung, Prime Minister, Vietnam, “Building Strategic Trust for Peace, Cooperation and Prosperity in the Asia-Pacific Region,” (keynote address, Shangri-La Dialogue 2013), at http://www.iiss.org/en/events/shangri%20la%20dialogue/archive/shangri-la-dialogue-2013-c890/opening-remarks-and-keynote-address-2f46/keynote-address-d176.

21 “Paracels build-up a pointer to China's broader South China Sea ambitions,” at http://mobile.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN0VT0YA.

22 Tran Truong Thuy, “The South China Sea: Interests, Policies, and Dynamics of Recent Developments,” (paper presented at the conference titled “Managing Tensions in the South China Sea” held by CSIS in Washington DC., on June 5-6, 2013), available at https://csis.org/files/attachments/130606_Thuy_ConferencePaper.pdf.

23 Author’s interview with senior researchers of the Diplomatic Academy of Russia, Moscow, January, 2014.

24 “Beijing rejects Hanoi's legal challenge on Spratly, Paracel islands disputes,” http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1661364/china-rejects-vietnam-claims-arbitration-submission-over-south-china-sea.

25 http://www.mofa.gov.vn/en/tt_baochi/pbnfn/ns160712211059.

26 “Exclusive: Vietnam PM says considering legal action against China over disputed waters,” http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/05/21/us-vietnam-china-idUSBREA4K1AK20140521.

27 “Vietnam's PM calls for preparation of lawsuit against China,” at http://www.thanhniennews.com/politics/vietnams-prime-minister-calls-for-preparation-of-lawsuit-against-china-27986.html.

28 However, it takes time for Vietnamese Navy in building a full-fledged submarine capability as it requires not only machines itself, but also concerted effort in investing in infrastructure, maritime aerial surveillance, proficient crews, submarines rescue capabilities and international cooperation with regional navies. See, Koh Swee Lean Collin, “Vietnam’s New Kilo-class Submarines: Game-changer in Regional Naval Balance?” at http://www.rsis.edu.sg/publications/Perspective/RSIS1622012.pdf.

29 “Vietnam builds naval muscle,” The Asia Times, March 29, 2012, at http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Southeast_Asia/NC29Ae01.html.

30 Carl Thayer, “With Russia’s Help, Vietnam Adopts A2/AD Strategy,” The Diplomat, October 8, 2013, at http://thediplomat.com/2013/10/with-russias-help-vietnam-adopts-a2ad-strategy/.

31 For information on Vietnam’s Major Defence Acquisitions since 1995, see, Le Hong Hiep, “Vietnam’s Hedging Strategy against China since Normalization,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 354-355.

32 Defence White Paper 2009, p. 24

33 “Ra mắt lực lượng Kiểm ngư Việt Nam” (Launching Vietnam Fisheries Resources Surveillance force, Government’s Website), at http://baodientu.chinhphu.vn/Hoat-dong-cua-lanh-dao-Dang-Nha-nuoc/Ra-mat-luc-luong-Kiem-ngu-Viet-Nam/197269.vgp.

34 “Chinese vessels deliberately ram Vietnam's ships in Vietnamese waters: officials,” at http://tuoitrenews.vn/society/19513/chinese-vessels-deliberately-rammed-into-vietnamese-boats.

35 “Japan Coast Guard vessels and equipment in high demand in S.E. Asia, Africa,” the Asahi Shimbun, September 30, 2013, at http://ajw.asahi.com/article/asia/around_asia/AJ201309300001.

36 “Japan to supply six ships to Vietnam, intended for patrolling: sources,” at http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/08/01/national/japan-supply-six-ships-vietnam-intended-patrolling-sources/#.VGYZwigp-fQ.

37 AP, “US boosts maritime security aid to Vietnam,” at http://news.yahoo.com/us-boosts-maritime-security-aid-vietnam-082842052--politics.html.

38 Prashanth Parameswaran, “US Delivers Six Patrol Vessels to Vietnam in Defense Boost,” May 25, 2017, at http://thediplomat.com/2017/05/us-delivers-six-patrol-vessels-to-vietnam-in-defense-boost/.

39 “U.S.-Japan Joint Statement: The United States and Japan: Shaping the Future of the Asia-Pacific and Beyond,” at http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/04/25/us-japan-joint-statement-united-states-and-japan-shaping-future-asia-pac.