Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, international interdependence is changing. The current international political situation, characterized by harsh power politics, and the current state of the international economy, in which states with different values are economically connected, are leading to reconsideration of international supply chains. Understanding international supply chains is extremely important in looking at the prospects for the global political economy. The purpose of this comment is to explore the trends and implications of reconsidering supply chains.

Supply chain vulnerabilities and concerns

All nations' economies are embedded in international supply chain networks. Cross-border supply chain networks bring not just benefits but also risks to the companies that depend on them and to the countries where those companies are based and their products delivered. Shutdowns of corporate facilities and factories, stay-at-home orders, and export restrictions hamper research and development (R&D) and parts production in the lower tiers of supply chains. Supply chains may be disrupted, for example, by the closure of factories in China, the suspension of parts supply, and business continuity difficulties faced by subsidiaries in Thailand. Halted production of the core electronic components in digital products can cause instability in the supply of final products. If there are only a few component manufacturers in some industry sector, business suspensions or bankruptcies among those suppliers will have a negative impact on entire supply chains. Shocks that directly impact manufacturing capacity in the lower tiers of a supply chain can affect the entire supply chain network.

The fragility of modern supply chains goes beyond the manufacturing dimension. Transportation delays also highlight current supply chain vulnerabilities. Shocks to supply chains in the transportation dimension can be caused by decreases in the number of flights and delays in paperwork due to staff teleworking, among other reasons. The resulting stagnation of supply from lower tiers to upper tiers in supply chains leads to delays in the delivery of finished products. These supply chain vulnerabilities in the transport dimension have exposed the risks associated with the just-in-time production system, which is based on short-term delivery. The supply chain mechanism for short-term delivery of products allowed global companies to make more profits, but it increased supply chain risk. This is because globalization has promoted a just-in-time production system based on the international division of labor, and companies have cut their inventories to the limit. Delivery delays caused by the new coronavirus have disrupted the flow of goods that rely on international supply chain networks, and the validity of the just-in-time production system is being reassessed.

The potential risks in international supply chains are garnering attention as one example after another emerges of countries introducing border controls that prevent the procurement of protective equipment and respirators. As international economic interdependence works across borders, it is difficult to keep that interdependence from the influence of sovereign states with the right to control borders. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), 80 countries had introduced new export prohibitions and restrictions as of late April. The products covered by these measures include medical supplies (e.g., facemasks and shields), pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment (e.g., ventilators)1. Under these circumstances, it was once again recognized that it is serious for the state to have difficulty in obtaining critical emergency goods during times of crisis. With the civil aviation sector having been severely impaired by the new coronavirus crisis, serious concerns are now emerging about damage in the civilian sector spilling over into the defense industry.

On the other hand, there has also been a growing concern that international interdependence means states may have leverage over and/or be vulnerable to their international political competitors. Negative types of interdependence increase tensions and friction, with one side using asymmetric structure of interdependence to exert influence over other countries2. Against the backdrop of the current competitive international political situation, an alarm has once again been raised about the use of cross-border supply chain controls by other countries. There are concerns about economic interdependence being weaponized.

These concerns have been particularly felt in dealings with China. Even before the new corona crisis, it had been pointed out that China has used economic leverage to influence the liberal democratic powers. China has arguably created an asymmetric economic dependence with other powers in pursuit of its diplomatic and political goals3. With America's leadership in the global fight against the new coronavirus seemingly fading, it has been argued that China was seeking to establish its international leadership by touting its anti-virus success, promoting its domestic governance model, and providing material support to other countries. At that time, it was pointed out that Beijing's edge in material assistance stemmed from the fact that much of what the world depends on to fight the novel coronavirus is made in China4. China's supply of medical equipment and pharmaceuticals, called "mask diplomacy," has triggered alarm over China's growing influence overseas. It has also been asserted that Beijing's "mask diplomacy" will put pressure on countries that are reluctant to adopt Huawei products for their fifth-generation mobile communications system (5G) infrastructure5.

Mitigating vulnerability

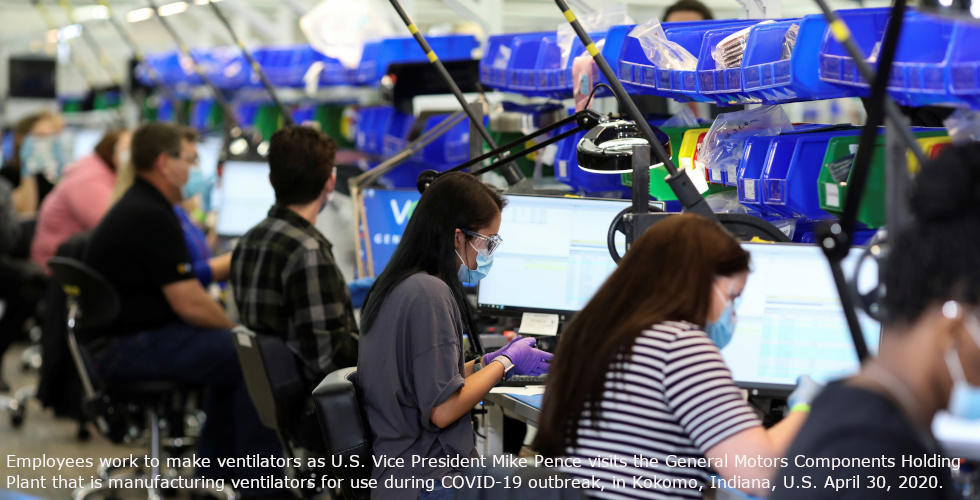

Against this backdrop, measures are being taken to reduce supply chain vulnerabilities. These efforts also aim to mitigate the aforementioned concerns. First, there have been calls for reshoring to lessen vulnerabilities in the manufacturing dimension of supply chains. The most representative argument was made by Peter Navarro, the White House's trade and manufacturing adviser: "(I)t is important for the Trump administration to bring home its manufacturing capabilities and supply chains for essential medicines and thereby simultaneously reduce America's foreign dependencies, strengthen its public health industrial base, and defend our citizens, economy, and national security."6 In March, President Trump issued an executive order to use the Defense Production Act (DPA) to prioritize the production of materials necessary to respond to the new coronavirus and, under this order, he requested that General Motors Company (GM) accept, perform, and prioritize contracts or orders for ventilators7. Like the United States, many countries are promoting domestic production of medical supplies.

Others have taken steps to protect domestic manufacturing capacity. A typical measure is tightening regulations on inward foreign direct investment (FDI). The US government has already tightened regulations on inward FDI through revisions to the Foreign Investment Risk Assessment Modernization Act (FIRRMA) and, with the onset of the novel coronavirus crisis, similar measures are being adopted in other countries. For example, in Australia, regulations on foreign investment have been tightened through a change in the foreign investment framework, with all inward investments being subject to review by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) to ensure they are not contrary to the national interest8. Behind these efforts are concerns over the outflow of the manufacturing and technological bases of critical industries through mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The decline in stock prices due to the new coronavirus crisis further fueled these concerns. As noted above, measures have been taken in various countries to restore and maintain manufacturing capacity at home to reduce the fragility of supply chains in the manufacturing dimension. It is understandable that the United States is trying to attract Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (TSMC), the world's largest contract manufacturer of microchips, to set up operations in the US.

On the other hand, efforts are being made to enhance the resilience of supply chains by decentralizing and diversifying supply chains. It is difficult for a country to build up its full manufacturing capacity in a short period of time, and it is not realistic to bring all industrial sectors back home because of the low wages available in developing and transit countries. In this context, the United States seems to be accelerating moves to restructure its supply chains, such as by shifting production bases in China to other countries. Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand and Vietnam and Latin American countries such as Mexico are prime candidates for the decentralization and diversification of production bases. The focus is on reducing excessive dependence on specific countries and eliminating bottlenecks in products and parts.

Approaches are also being developed to mitigate vulnerabilities in the transport dimension of supply chains. For example, it has been pointed out that just-in-time production relying on short-term delivery poses risks to modern supply chains, and that redundancy should be built into the economy9. However, ensuring sufficient redundancy in supply chains is no easy task for companies. Current supply chains are extremely streamlined, and inventory is a heavy burden for companies in sectors with short product lifecycles.

There were nonetheless some notable developments in the private sector. Nissan, for example, has begun production of medical face shields at its plants in Tennessee and Mississippi and its R&D facilities in Michigan. The company reportedly said it would produce 1000 units per week using 3D printers. Razer, a gaming company, announced plans to use its manufacturing line to make surgical masks and donate one million of them to medical professionals around the world. An Italian company, Isinnova, declared that it had reverse-engineered and 3D-printed ventilator valves, and delivered them to hospitals. In this way, some private companies are diverting their own facilities, technical resources and other assets to fill gaps in supply chains in different sectors. They complement existing supply chains by utilizing advanced technologies and contribute to the resilience of entire supply chains.

Conclusion

The new coronavirus crisis has highlighted the potential risks in international supply chain networks. Countries have therefore sought to overcome supply chain vulnerabilities. What we have seen above are such approaches as reshoring and maintaining manufacturing capacity and technological bases at home, decentralizing and diversifying supply chains, and using advanced technologies to complement supply chains.

Such efforts can also be seen in Japan. The Government of Japan allocated 220 billion yen in its supplementary budget for FY2020 to support the development of domestic production bases by companies, etc., for important products and materials. In addition, the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Control Law has been revised to tighten regulations on inward FDIs, such as by revamping the scope of prior notification (effective from May 8). In response to the new coronavirus crisis, medical equipment will be added to the products covered. These measures are aimed at bringing home the manufacturing and technological bases of important industrial sectors. Japan is also bolstering partnerships with ASEAN and other countries to further promote supply chain diversification. The Japanese government allocated 23.5 billion yen in its supplementary budget for FY2020 to support the diversification of manufacturing bases by companies in ASEAN countries. In April, Japan and ASEAN announced the "ASEAN-Japan Economic Ministers' Joint Statement on Initiatives on Economic Resilience in Response to the Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak". In addition, efforts by private companies should not be overlooked. Ricoh reportedly announced in April that it had started 3D printing production of face shields that prevent droplet infections, and that it would provide these to designated medical institutions for infectious diseases10.

It is still unclear how the post-corona world will look. However, efforts to reconsider and rebuild supply chain networks as discussed in this essay will undoubtedly continue. Arguments for decoupling from China in the fields of advanced technology and industry had been put forth even before the outbreak of the novel coronavirus crisis, but the current debate is not simply one over a choice between withdrawing from China and strengthening involvement with China. Rather, the focus of discussion is on what supply chain networks should be built in which sectors and with which actors. In doing so, the sharing of advanced technology to complement existing supply chains as described above will also be an issue to be considered. Therefore, efforts to reconsider and rebuild supply chain networks may strongly mirror the current competitive international political dynamics.

(Dated May 11, 2020)